The Royal Standard of England: A Living History

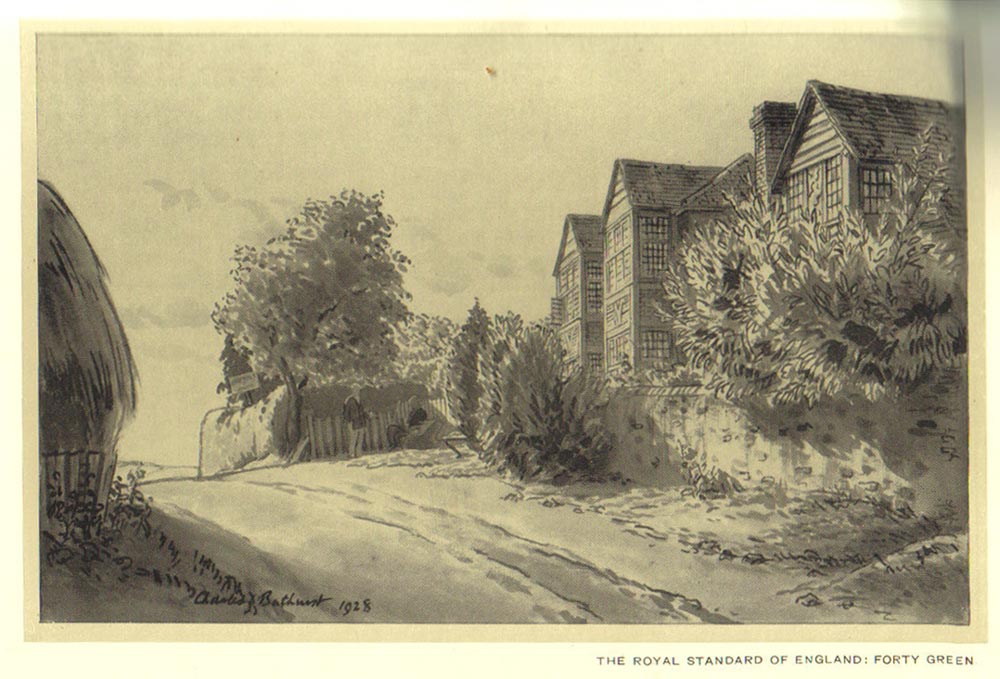

Step inside The Royal Standard of England, and you’re not just walking into a pub, you’re entering a living story that began nearly a thousand years ago. Nestled in the rolling hills of the Chilterns, this ancient inn has survived war, invasion, ghosts, kings, rogues, and revelry. But more than anything, it has endured because it remains what it always was: a place for people to gather, share stories, drink ale, share a meal and make history of their own.

Roman Roots and Saxon Settlers

Long before beer flowed from our taps, the Romans fired bricks and tiles in kilns right across the fields from the pub. Walk the nearby paths toward Lude Farm, and you’ll still find shards of Roman tiles in the soil—remnants of an industry that lasted for 1,400 years.

After the fall of Rome, Saxon ex-legionaries and Germanic settlers moved in. They brought with them their love of ale, barley farming, and the ancient tradition of the Alewife, a woman brewer who would raise a green bush on a pole to announce that the brew was ready.

This very site, rich with spring water from an old Romano-British well, became a brewing ground for King Alfred’s West Saxons. The alewife’s parlour naturally became a meeting house because she was the best village ale brewer. The cottage that housed the brew became the alehouse, a communal meeting spot for cottagers, tile-makers, and drovers who worked the land together. Beer was safer to drink than water in those days, and in many ways, we think it still is.

Vikings, Normans and the Birth of The Royal Standard of England pub

England became a patchwork of Celtic Britons and Anglo-Saxons until the Vikings came in their longships. In 1009 and 1010, they sailed up the Thames and raided nearby Hedsor Wharf. But our alehouse survived—tucked safely away from the water’s edge.

The alehouse sat just outside the vast Lude Estate, home to the powerful Godwine family. One of them, Earl Harold Godwine, became King Harold II, who famously fell at the Battle of Hastings in 1066. The Saxon alehouse became known as “Se Scip” (The Ship) Saxons liked giving people and places nicknames, the new local lord was Remi the Norman Bishop warrior. He was rewarded by William the Conqueror these local lands for supporting the military invasion with a supply of ships.

When the Normans arrived, they didn’t settle here; life at the alehouse went on unchanged. Lude Farm, just 1000 yards west of the pub is also listed in the Domesday Book in 1086 our alehouse was able to carry on its trade as usual. In 1213, it was officially recorded as The Ship Inn, serving the Royal deer hunts. The Norman Kings would move the whole medieval court between Windsor Castle, Wallingford and Woodstock Palace, using the alehouse as a lodging place and a watering stop for transporting tiles by carts for Windsor Castle and the Palace of Westminster and livestock drovers bound for Markets in London.

Middle Ages

The tile merchants and animal drovers provided good trade for the alehouse. The large cattle drives moved stock down the drovers' roads to the rich fattening pastures, on to markets in Beaconsfield and Wycombe, and eventually London.

This procession passed by the pub which provided wells for watering the pack animals and ale for the drivers. Using these lanes avoided the fees at the Beaconsfield Turnpike on the Oxford to London road.

The roads were also more dangerous to travel due to thieves and robbers. Indeed, a decree was passed in 1304 (during the reign of Edward I) that all brushwood should be cut back to 200 yards either side of the road as a precaution against ambush.

Before the building of railways, the drovers' routes were trodden by tens of thousands of cattle, sheep and geese. The lane to Holtspur has been worn by mostly brick tiles laden ox carts into a “hollow-way” - a deep lane still showing its high banks, known as Riding Lane .

At the end of each drive a canny Welsh drover, named Thomas, would sell his valuable droving dog at the great London fairs for a good sum. He would then wait at the pub knowing the dog would find his way back to him at the first opportunity!

The alehouse’s customers were the working and independent folk who would create their own entertainment. Their revelries held at the alehouse avoided the prying eyes of the local officials. The pub is built between legal jurisdiction boundaries.

In 1485, a troupe of dancing men held a dance at the pub to celebrate Henry Tudor becoming king after The Wars of the Roses.

Ale, Rebellion & the Civil War

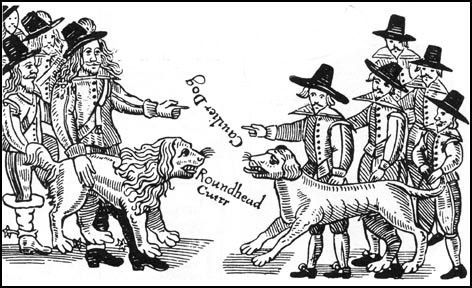

The pub was used as a mustering place for the Lord Wentworth’s Royalists before the Battle of Wycombe Rye in 1642. King Charles I had raised his personal standard to draw his royalist supporters (The Cavaliers) to fight for his cause against the Parliamentarians (The Roundheads).

The pub had connections with the Confederate Irish and catholic swordsmen, coming over to fight for the Royal Stuart cause. They were disliked by both sides on religious grounds. In November 1642 they were part of a Cavalier army led by the dashing Prince Rupert who captured Brentford. The following day they were turned back at Turnham Green by the greater Roundhead army. The Roundheads are thought to have camped in the field near Hogsback Wood, along the lane. (Now Roundheads Wood)

The area mostly under Parliamentarian control, suffered the brutality of the Roundhead soldiers, as a dozen Irish Confederate cavaliers had their heads raised up on pikes outside the pub’s door. This included a 12 year old Drummer boy. His ghost still haunts the pub today.

In 1643, a troop of the Earl of Essex’s Roundheads discovered an Irish Confederate Royalist captain, sleeping off his lunch in the pub. When captured by the Roundheads and having given his word not to escape, he is purported to have stood up one morning and said “Gentlemen, I give you notice - “I’m off “. He then jumped out of a window to freedom, considering that the ‘notice’ cancelled any previous undertakings!

With the King in his Oxford headquarters, the pub was on the quieter back route for messengers passing unnoticed through the lines. Cromwell’s New Model army strengthened the power of the Parliamentary side and the King was facing defeat. Royalists used the inn, trusting the loyalty of the landlord. Over time a local legend holds that King Charles I leaving Oxford spring of 1646 stayed in the pub on the way to Uxbridge.

After Charles II’s restoration to the throne, the pub was rewarded by the new king in 1663 for giving support to his executed father. He honoured the petitioning landlord by agreeing to change the name of the pub from ‘The Ship’ to ‘The Royal Standard of England’, the only pub in the country with the honour of the full title, and echoing back to the royal Wessex Royal Standard white dragon.

Though the royalists were well served by the landlord during the civil war, a more human reason emerges for the royal gesture for the pub’s name change. King Charles II was obliged to the landlord while he met his mistresses in the rooms above the pub. The shrewd landlord, with business in mind, had perhaps cashed in on his royal guest.

Highwaymen, Rakes and Outlaws

After the Battle of Worcester, a royalist trooper named James Hind, without a king or a cause, took to a life of crime. Hind began to rob the committee representatives appointed by Parliament to govern the counties. To avoid the attention of robbers, one committee member dressed himself with a worn out coat and kitted out an elderly horse in the cheapest gear. When he encountered Hind, the highwayman took him at face value, as the broken down old fellow he appeared to be, and gave him a gold piece. However, once he arrived at the inn, he was stupid enough to boast of his escape, and cursed Hind for a rogue. Our inn is where Hind was often put up. When he arrived later that evening, after the committee man had gone to bed, he was told what the man had said of him. The next day, Hind stopped the man on the road and robbed him of £50.

Hind insisted he never robbed the poor and had a habit of handing out magnificent tips to the peasants who supported the king. In order to hide their whereabouts, highwaymen used to reverse their horse shoes. Hind avoided capture by improving this technique with the use of circular horse shoes (There is one on one the bar beam). However, he was later caught, and taken to Worcester to be hung, drawn and quartered for treason (not robbery!) in 1652.

Even King Charles II praised “Swift Nick”, the gentleman rogue, for his ride from London to York in 1676. This was a feat mistakenly attributed to Dick Turpin in popular legend.

Highwayman had many accomplices among people who were outwardly respectable. Some of these were innkeepers. It was usual for guests who stayed at an inn overnight to leave their money in the care of the host. The landlord or his servants would tip off the robber as to which of the day’s travellers would be worthwhile to ambush on the road. After all, he would make much more money from the highwayman than ordinary guests.

Inn-keeping was profitable in the early 1700’s in an age when to be a publican was a near admission of corruption, if not criminal tendencies. At the beginning of the 18th Century, the pub as we know it today was a very different place. In the smoky, sweaty candle-lit atmosphere of most alehouses and inns; whoring, drinking and gambling went on all night. The quantity of spirits drunk in these taverns was enormous. Hogarth’s ‘Gin Lane’ was not considered exaggerated by his contemporaries, and the details of the scene were indeed taken from real life. The sign over the doorway bears the well-known legend: “Drunk for a penny, Dead drunk for two pennies, Clean straw for nothing.

The Restoration dramatist Nathaniel Lee drank himself into the ‘Bedlam Hospital for the Insane’ where he declared: “‘They said I was mad; I said they were mad; damn them, they outvoted me”.

He was eventually released but on the day of his death he drunk so hard, that he dropped down in the street , and was run over by a coach.

The inn’s trade declined in the mid-18th century as the brick trade moved elsewhere. It reverted back into an unlicensed alehouse on Admiral Lord Howe’s Penn estates.

It was restored to health through supplying the rail-workers with illegally strong country ale – Owd Roger. The beer was made of an old recipe, brewed for 500 years. It was eventually sold on to the Marstons brewery, but recent successive short term Governments have taxed it out of existence!

Ghosts, Witches and Wartime Echoes

Not all spirits are dead, some simply walk between worlds. In the pub, you can feel the strange overlap where past and present brush against each other.

Just down from the pub lies Riding Lane, a time-worn track hemmed in by high hedge-banks and overhanging trees, its earth pressed low by centuries of drovers’ ox carts. There is a sunken hollow here, known as the Hag Pit, long linked to witchcraft and local folk magic. For generations, it served as a hidden gathering place for hedge witches and hedge riders, those who practiced the arts of crossing boundaries, moving between the seen and unseen, belonging to both and to neither.

Terry Pratchett, creator of Discworld, lived in nearby Beaconsfield. He wandered these lanes and woods, and was a regular at the Royal Standard of England pub. His fictional worlds are full of thresholds—liminal spaces where the natural and supernatural meet, where time twists back on itself, and memory lingers like mist in the air.

The Royal Standard of England itself is a living reminder of the past’s persistence in the present. Hidden charms still whisper from its beams and corners, and in its rooms you might almost believe that history has never truly left.

In 1944 a US B-17 Flying Fortress, nicknaked the Tomahawk Warrior, crashed just over the road, claiming the lives of all nine crewmen. Witnesses today report the sound of bomber engines droning overhead, on clear nights when no planes fly.

Staff speak of candles extinguishing themselves, laughter from the empty cellar, and a woman's voice singing softly from nowhere. Could it be one of the pub's "cunning women", a healer or herbalist who once kept the fire of folk knolwege alive beneath the alehouse roof?

Still Serving Pilgrims

Through centuries, wars, raids, revolutions, and railroads, The Royal Standard of England has never stopped serving ale,

Some say you can still hear the drummer boy’s ghost at night, feel the breath of history in the beams, or spot a flicker of a royal guest in the shadows.

But we’re not a museum—we’re a pub. A warm, welcoming, ale-loving, history-rich pub where every pint poured adds another page to the story.

Come for the ale and vittles. Stay for the story, where the past is always present.